From time to time, my ire is raised by things I read. This is, perhaps, a bad thing – though there are those who argue, the Rambam believes that anger is never justified. Clearly, I am far from a perfect person.

From time to time, my ire is raised by things I read. This is, perhaps, a bad thing – though there are those who argue, the Rambam believes that anger is never justified. Clearly, I am far from a perfect person.

R. Shmuly Yanklowitz recently penned a harsh diatribe against R. Hershel Schachter wherein R. Yanklowitz attempted to marginalize R. Schachter by citing some curious statements R. Schachter has made over the years; in effect, he seems to say that R. Schachter is not fit for leading a Torah community. In the process, R. Yanklowitz – seemingly eager to make his point – drags up ancient (sometimes spurious) complaints against R. Schachter which, I suppose, are designed to vilify him in the eyes of the reader.

As I said, my ire was raised. My problems with this screed were multitudinous; as such, I’ll be going through it bit by bit, with R. Yanklowitz’s words in bold and mine in this standard font.

Here goes:

Recently, a scandal emerged within the Orthodox community when Rabbi Hershel Schachter, a halakhic leader and member of the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS), made an overtly racist comment that was recorded at a London conference.

R. Schachter made a(n almost certainly off-the-cuff) statement that could be taken in numerous ways. Some people thought it racist; others thought it was a slip of the tongue which he “corrected in the same sentence.” That said, I have trouble swallowing that the comment was “overtly racist.”

The greatest objections (including from Yeshiva University) revolve around his reluctance to sanction the reporting of sex crimes directly to the police (mesirah), warning that if a Jewish sex offender were sent to a state prison, he might be killed by the warden, or beput “in a cell with a shvartze, in a cell with a Muslim, a black Muslim who wants to kill all the Jews.”

It is true that we must be cautious to be sure that innocents are not thrown in jail. I recently made the case for how many mistakes our penal system is making in this regard. However, religious leaders are not the judges of who is guilty and who is not. We live in one of the most sophisticated judicial systems in the world, one of the reasons why Rabbi Moshe Feinstein argued that we live in a “medina shel chesed” (a nation of kindness) where on the whole we can trust the judicial system.

I would assume that R. Schachter would agree with this assessment of the judicial system. In fact, he shows little hesitation in turning alleged criminals over to the judicial system.

Rabbi Schachter admitted that decades ago a Yeshiva University High School student confided that he had been abused by a Yeshiva administrator. While the details are in dispute, Rabbi Schachter did not follow up on the investigation, and the administrator in question continued to abuse students for years afterward.

This seems to be a rather unfavorable description of R. Schachter’s actions.The Forward writes “Schachter said that he asked the student to tell his story to a rabbi who served as the school psychologist…” which would seem to be the appropriate call. As R. Schachter was (we can assume) not very experienced with abuse cases, he referred the student to a mental health professional, which would seem to be the proper course of action.

While acknowledging in his talk that there is no violation of the halakhah in allowing mesirah for child sexual abuse and most other crimes, Rabbi Schachter then weakened the argument. He proposed that a board of Torah scholars should first hear the charge to determine if there were raglayim l’davar [a credible charge requiring a report to the police], as a child’s report of abuse could be made up (a “bubbe-mayse”).

R. Schachter actually said that a board of psychologists should first hear the charge. (See what I did there?)

He also demeaned the student who had reported the initial abuse to him: “So now, 40 years later, the guy’s spilling everything out to the newspaper.”

I’m not sure how this is demeaning. He was presumably trying to say that there is little to gain by talking to newspapers about crimes committed 40 years ago. I don’t know if he’s right, but I’m not sure how that’s demeaning.

He further stated that it was the student’s responsibility to follow up with the school psychologist, and if he did not he bore the blame for any further abuse that occurred at the high school.

I might be wrong, here, but I think R. Yanklowitz – just a few sentences ago – tried to intimate that it was R. Schachter’s fault that further abuse occurred at the school.

Put yourself in R. Schachter’s shoes for a moment. He’s not a youngster, but he’s not ancient, either. 40 years ago, he was a rather young, relatively inexperienced faculty member. A student came to him and accused one of R. Schachter’s colleagues of abuse. When R. Schachter – ill-equipped to deal with this issue and uncertain as to the veracity of the claim – suggested that the student speak to a mental health professional, the student backed off. The student – assuming he was telling the truth (and I’m not suggesting we assume either way) – knew that there was an abuser on the loose. R. Schachter didn’t.

I thank G-d that I was never abused and don’t know the trauma involved, but from my vantage point, I hear where R. Schachter is coming from.

We need Modern Orthodox leadership that represents the sacred moral values of our Torah!

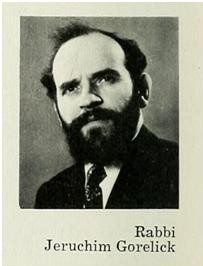

Rabbi Schachter’s prowess as a Torah scholar is extraordinary.

I think this is true. Let me cite a bit from a Jewish Journal article to demonstrate. The article at this link, which seems to piggyback on a legal stringency of R. Schachter refers to him as “one of the greatest Jewish legal authorities in America” and “the leading rosh yeshiva at Yeshiva University [who] is a halachic adviser to the kashrut division of the Orthodox Union and is unwavering in his commitment to the integrity of Jewish law.” Curiously, the author of that article is one R. Yanklowitz

At age 22, he became the assistant of the noted Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, z’l, and at age 26 became the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since then, he has written and taught extensively on Talmud and Jewish law. Even the student who confided in vain about sexual abuse acknowledged that Rabbi Schachter was a “true Gadol B’Yisroel (giant of torah).” Further, Rabbi Schachter’s reputation as a man who is kind, sensitive, and sweet in most of his interpersonal dealings is surely warranted.

I’m vacillating about whether the student’s respect for R. Schachter is relevant. I think we could interpret his statement to mean that he believes that R. Schachter is a great man who erred, not that R. Schachter – in general – is not a good example of Torah leadership. I find it interesting that this person who suffered so much seems to be willing to look at all sides of a person before speaking against him.

A teacher has responsibilities beyond instructing content and disciplinary method. We teachers have a responsibility (second to parents) in molding children – an appreciation for faith, ethics, and other healthful values. When a student confides in us, it is our responsibility to consider what is good for the child and to act upon those considerations.

Is there a point to this educational philosophy. Are we to assume that R. Schachter cares little for the faith (!), ethics (!) and health of his students. I don’t think so. I may be misreading this, but it seems to me that R. Yanklowitz feels that R. Schachter erred and is attempting to paint R. Schachter as an uncaring, poor educator rather than an educator who made a mistake.

This case is indicative of an unfortunate tendency of some Modern Orthodox educators who have moved to an ultra-Orthodox position that can obstruct justice. It must be acknowledged that sexual abuse was tolerated at Yeshiva University for years, and that several well-known administrators and faculty, even after their guilt was established, were allowed to resign and move on to other positions in youth education rather than face sexual abuse charges or even social or professional cost. Furthermore, even if Rabbi Schachter’s claim that he told the student to go to the school psychologist is true, he should have realized that many in the Orthodox community considered it shameful (and still consider it so today) to go to a psychologist, and so it was unlikely that a student would go there with a story like this.

Ah! And nobody in the Orthodox community considers it shameful to take a rabbi to the police, so of course that was the perfect solution! (R. Yanklowitz, if you’re reading this, I really don’t understand you.)

To establish layers of bureaucracy or throw blame on the victims is to hurt the students who are supposed to be served by institutions of learning.

This trend can also lead to intellectual isolation. I remember I was once at a Friday night tisch when I was a graduate student at Y.U. and a student asked Rabbi Schachter if he was allowed to study English literature. Rabbi Schachter responded that he could, as long as it was for parnassah (supporting his livelihood), but not because there was any value to this learning – this occurred not at Ponevezh or the Mir, but at Yeshiva University, the center of Torah U’Madda (the integration of religious and secular studies)!

We seem to have reached the “enough with abuse, let’s bash R. Schachter for various things he has said over the years” segment of this article.

Rabbi Schachter’s obtuse desire to ignore the world outside of his personal focus may help explain his many notorious statements. In the London speech referred to above, for example, he raised no objection to sending a Jew to a federal prison, since they have kosher food and better conditions (and presumably less menacing clientele than in state prisons).

Basically, R. Schachter has a broad understanding of “cruel and unusual.” And this is because of his obtuse desire to ignore the outside world?

Consider the following examples:

• In 2004, when asked about the question of women reading a ketubbah at a wedding, he replied that a wedding was valid even if “a parrot or a monkey” did the reading, which angered many women’s groups.

R. Yanklowitz is right that this is a notorious statement; I think he’s right that it angered women’s groups.

• In 2008, he reportedly told a group of yeshiva students that if any Israeli government would “give away Jerusalem,” then the Israeli prime minister responsible should be shot.

I’m going on memory here, but I believe I heard a recording of this notorious statement. After he said it, everyone laughed. In other words, not only was it a joke, it was recognized by those who actually heard it as one.

• In August 2012, Rabbi Schachter was criticized by the Board of Directors of the Council of Centers on Jewish-Christian Relations for accusing some Orthodox rabbis in Israel of promoting idolatry (avodah zarah) and conversion from Judaism (shemad) by teaching Gentiles about Judaism, ignoring and perhaps threatening decades of progress in Christian attitudes toward Jews and Israel. Abraham Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, stated that Rabbi Schachter “seems to know nothing about the different Christian denominations or the current state of Jewish-Christian relations,” and lamented “that a religious figure and university academic who is well respected in the Yeshiva world would publish such a distorted and error-filled text which promotes negative attitudes.”

I don’t know much about this; if I’m understanding this correctly, R. Yanklowitz had determined thus far that R. Schachter mishandled one situation forty years ago and has made three offensive statements in the last decade. (By my tally, one was a joke, and was only offensive to those with excessive wax buildup in their ears.)

While teachers may have areas of concentration in their studies, they should welcome the opportunity of learning something new, and passing it on to their students. Rabbi Schachter, especially due to his prominent position, owes his students the finest education available, without racist vocabulary and trivializing sexual abuse.

I have never heard any indication whatsoever (except from this article), not even the slightest bit, that R. Schachter trivialized sexual abuse. (It is also fair to point out that these quotes were not made in school.)

Louis Brandeis was an admirableJewish scholar dealing with justice and society. As the first Jewish associate justice of the Supreme Court, a Zionist, he was a tireless proponent of the social welfare. Brandeis understood that secular institutions such as the courts could help secure the liberty of the people, and that it was incumbent on citizens to guard their liberty. In addition, he established a legal precedent of filing court briefs (called “Brandeis Briefs”) that combined legal, economic, and sociological data to advocate better working conditions and other worthy causes. Consider the wisdom of an intellectual who also acted in the public interest:

• “Neutrality is at times a graver sin than belligerence.”

• “Our government … teaches the whole people by its example. If the government becomes the lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for law…”

• “The greatest dangers to liberty lurk in the insidious encroachment by men of zeal, well-meaning but without understanding.”

We now have quotes from an American Jewish jurist. Two of them speak in favor of following the law (one, perhaps other action) and one speaks about the dangers of well-meaning people without understanding. (In all fairness to this segment, I do like the name Louis.)

Yeshiva University deserves credit for publicly rebuking this rosh yeshiva who has crossed the line of offensive rhetoric once again. The Torah demands that we see the dignity in all humans and that we be honest and forthright in all of our ways.

I’m actually glad R. Yanklowitz brought up honesty; I wasn’t going to ask this before but now I will: Would R. Yanklowitz have rather R. Schachter lied about his feelings on literature.

One who uses racist slurs and impedes justice for abuse victims does not represent the Torah community.

Is it accurate to say that R. Schachter uses racist slurs?

I’m going to assume that R. Yanklowitz means abuse perpetrators, though I highly doubt R. Schachter has any intention of impeding justice for either of them.

We honor Torah scholarship and we respect the good intentions of sincere men and women, but the Modern Orthodox community needs moral leadership deeply sensitive to contemporary human needs and responsible in legal and ethical discourse.

I might even addend that if we had leadership that was “deeply sensitive” to critical discourse that would be nice, too.

From time to time, my ire is raised by things I read. This is, perhaps, a bad thing – though there are those who argue, the Rambam believes that anger is never justified. Clearly, I am far from a perfect person.

From time to time, my ire is raised by things I read. This is, perhaps, a bad thing – though there are those who argue, the Rambam believes that anger is never justified. Clearly, I am far from a perfect person. 1. Answer this: Is there any day of the year when there is more chillul hashem than Purim?

1. Answer this: Is there any day of the year when there is more chillul hashem than Purim? Once again, I’m going to be posting about the Weberman trial…so sue me. There were various reasons for the opposition to some of the proceedings. Some people felt that the trial wasn’t fair. I’ve

Once again, I’m going to be posting about the Weberman trial…so sue me. There were various reasons for the opposition to some of the proceedings. Some people felt that the trial wasn’t fair. I’ve

Towards the beginning of this week’s parsha (Exodus 18:13-27), something rather interesting occurred. Yisro, who had just joined the Jewish nation, observed Moshe acting in a manner that the fromer found troubling. Moshe, as leader of the Jewish people, was personally adjudicating disputes from morning to night.

Towards the beginning of this week’s parsha (Exodus 18:13-27), something rather interesting occurred. Yisro, who had just joined the Jewish nation, observed Moshe acting in a manner that the fromer found troubling. Moshe, as leader of the Jewish people, was personally adjudicating disputes from morning to night.